In the world of everyday computer technology, we know that the adjective "smart" (as in smartphone) refers to a flexible system that performs a variety of tasks on demand. My smartphone can be a camera, a calculator, a music player, a video chatting device, or an internet portal. If it were intuitive, like the car I don't yet own, it would automatically adjust its suspension for varied terrain or steer itself back onto the road if I dozed, without even requiring my input to maintain my comfort and safety.

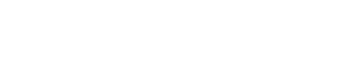

But my smartphone can never turn into my smart car, though they may share similar programming systems. Matter is, finally, stable. Unless you're a robotics scientist at MIT's Distributed Robotics Lab (DRL) working on the development of self-reconfiguring robots that actually can change their shape. Imagine many tiny cubes, each one a folded up electromagnetic micro processing unit capable of bonding with its neighbor. Right now these cubes are 1cm on each side, down from their predecessor's 4cm. Now imagine them at 1mm, like a grain of sand. Smart sand, as the cubes say on each side. Or, to use another metaphor favored by MIT robotics professor and DRL Principal Investigator Daniela Rus: electronic clay. Because in remote or combat locales, sometimes what you need in your rucksack isn't a bunch of software but a bunch of things, tools, and objects to interact with the physical world.

(Photo of Smart Sand cubes courtesy of MIT Distributed Robotics Lab within the MIT Computer Science and Artificial Intelligence Laboratory)

A table or a screwdriver or a rope ladder is a useful thing to have in the backcountry, but better still are things that have some capacity to think for themselves about what they are doing. As any manager knows, assigning tasks is less ideal than delegating responsibility. Yesterday we blogged about Minnesota's Recon Scout robot, which is driven by a remote human operator who follows its progress on a screen. With the help of improved, adaptive robotic intelligence, the Scout could make its own decisions about which way to go. Made out of MIT's self-reconfiguring smart sand material, a recon robot like Scout could shift its physical shape to best traverse the landscape.

- Make them smaller

- Make them smarter

- Make them adaptive in configuration and function

Another creative form that MIT's reconfiguring robots are taking comes from Japanese origami. Instead of being made up of building block cubes, these origami-bots reshape like a single folded piece of paper. (Image at right, courtesy of MIT DRL)

Another creative form that MIT's reconfiguring robots are taking comes from Japanese origami. Instead of being made up of building block cubes, these origami-bots reshape like a single folded piece of paper. (Image at right, courtesy of MIT DRL)

Still other morphable robots link up not cube to cube but molecule to molecule. Each molecule is made up of two atoms and has 180-degree flexibility for reconfiguration and locomotion. (Image below, courtesy of MIT DRL)

But if all of this programmable matter leaves you feeling a little bereft, missing the clumsy but familiar anthropomorphic robots of the Jetsons and Carls Jr. commercials, you'll be relieved to learn that another team of MIT scientists are busy programming a Willow Garage PR2 robot to bake cookies. And what, really, could be more comforting and assistive than that? (Photo courtesy of MIT News)

But if all of this programmable matter leaves you feeling a little bereft, missing the clumsy but familiar anthropomorphic robots of the Jetsons and Carls Jr. commercials, you'll be relieved to learn that another team of MIT scientists are busy programming a Willow Garage PR2 robot to bake cookies. And what, really, could be more comforting and assistive than that? (Photo courtesy of MIT News)

The New York Times just published an article referencing the PR2, "In Search of a Robot More Like US." Computer Scientists at UC Berkeley are also at work trying to program a PR2 (which are made in Silicon Valley), and have had a similarly frustrating experience getting the machine to do something that is relatively mindless for a human being, in this case folding laundry. Watson may be able to win at Jeopardy, but motion and perception are a whole other matter.

MIT is one of six US universities chosen to participate in the President's Advanced Manufacturing Partnership, specifically the National Robotics Initiative component. (UC Berkeley is another.) With funding from the NSF primarily, the NRI is designed to fund robotic research that augments rather than replaces human labor and ingenuity, creating a symbiotic relationship between humans and machines. The cookie-baking PR2 is a programming experiment more than a prototype for a machine you're likely to ever see. But machines that physically assist humans in other ways, at manufacturing plants or in hospitals, physical rehab facilities or in warzones, are taking shape right now in university laboratories across the United States.

Q: When Professor Rus calls robotics "the next disruptive technology," what do you think she envisions?

If you are a scientist or lab equipment supplier to the life sciences in the Boston/Cambridge area, consider attending Biotechnology Calendar Inc.'s annual BioResearch Product Faire event on the MIT campus. The next event will be held in 2012, but check out our show schedule for the rest of 2011 on our website, here. Biotechnology Calendar Inc. produces premium marketing and networking events across the United States and throughout the year specifically for life science professionals.

For data on MIT and show information, click the button below.